|

The general population believes that most tree companies are focused on removal alone. While tree cutting is certainly a large part of our business in both Latham and Albany, our mission as a tree service is first and foremost to maintain a healthy landscape, which typically means a combination of trimming, pruning, and disease management for both residential and commercial tree care. Trees are a valuable resource that not only look great, but also provide clean air by generating fresh oxygen. Albany County is home to many different species of trees, which are described below.

Pitch pine (Pinus rigida) The medium-sized pitch pine, also known as a candlewood, torch or yellow pine, is native to the northeastern United States and populates pine-oak forests in the region. Like other pine trees, pitch pines produce needles (in bundles of three) and clusters of round cones, which each measure between one and three inches. After forest fires, populations of pitch pines can regrow and regenerate successfully and quickly. The species’ mature height is usually over 50 feet. Its soil requirements are minimal; pitch pines can grow on nutrient-poor, sandy soil. Find this and other varieties of pine tree by visiting the Albany Pine Bush Preserve, an inland pine barren formed by a melted glacier thousands of years ago. Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) This fast-growing forest staple in New England is big and mighty: it often grows above 100 feet in height, and is a favorite habitat of bald eagles. It produces medium-strength soft wood and its lumber is very commonly used to build houses and furniture. If left alone, an Eastern white pine tree can live hundreds of years, though logging in North America during the 1800s and early 1900s halted several generations of growth for the species. Only a small percentage of original growth from before the continent was colonized remains intact. Pine needle tea is made with this species’ needles, which come in bundles of five. Its cones are a bit longer and softer than other types of pine cones. White ash (Fraxinus americana) New York has the highest number of white ash trees of any state and is mostly found within damp, wet woods, in rich soil loaded with nitrogen and calcium. Find it alongside other strong tree species in the forest, like eastern white pine, northern red oak, white oak and sugar maple. Like other hardwoods, white ash is commercially valuable and used to build many things; notably, it’s the primary material for baseball bats and hockey sticks. Its branches feature thick twigs and short stems that connect to the sharp-ended leaves, which come in sets of five, seven or nine. Look out for winter buds sprouting at the end of each twig before leaves start to form in spring. When this tree is fully grown, specimens average 60 to 70 feet in size, occupying forest canopies and growing intently towards sunlight. Animals in the woods are known to graze on the tiny fruit seeds that fall in samaras to the ground, and small mammals like rabbits, beavers and porcupines sometimes eat the bark of young trees. More often, birds and mammals use these trees in the forest as protection from harsh weather and predators. Sadly, this critically endangered species has been dying off due to urban pollution and the invasive Emerald Ash Borer beetle, which has annihilated specimens across North America. Compared to similar ashes, like blue ash, white ash is very weak at defending against the bugs, which eat through the bark and reproduce rapidly in the canopy. The Emerald Ash Borers leave distinctive, tiny D-shaped holes in the bark and then larger S-shaped patterns in the meat of the tree. Beetle larvae, after years of damage, will split the tree apart; woodpeckers also feast on larvae and cause more damage by hammering away. Yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) Yellow birch grows throughout New York State alongside sugar maple, ashes, gray birch and eastern white pines in hardwood forests. The species can be distinguished by its yellowish-gray trunk, which with age peels back in thin, papery layers. Its leaves are wide and flat with a “hairy” undersurface, especially along the veins. Yellow birch wood is incredibly heavy and hard, making it a good candidate for use in furniture, flooring, agricultural equipment and kindling. Trees can measure anywhere from 60 to 100 feet in height, and the average lifespan for yellow birch is 150 years (although they grow slowly). The species provides nourishment to many: deer like to “browse” birch twigs, squirrels eat seeds, and beavers and porcupines are known to chew on yellow birch bark. Seeds are also eaten by songbirds and grouse. Gray birch (Betula populifolia) Less common than yellow birch, gray birch is found only in the far northeastern areas of the United States and Canada, and in New York, only in the east of the state. It is not a tree that requires much from soil, and so populates soil-poor areas like clearings, burnt ground and abandoned, unusable farmland. Relative to other trees on this list, gray birch has a limited lifespan. Its gray, slightly scarred trunk does not get as thick as other birches and its total height does not exceed 30 feet. After a forest burns down or undergoes clear-cutting, ecologists use gray birch as a “pioneer species” that sets the stage for new forest growth, giving way to larger and longer-living tree varieties. Its symmetrical leaves taper out from a wide base to a narrow tip at its end, forming what looks like a cross between a triangle and a heart shape. White oak (Quercus alba) Not to be confused with swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), white oak is a mighty wood source found in isolation or in forests. When it’s part of a thicket, one of these oaks can exceed 90 feet in height competing with other treetops in the canopy. Used for heavy-duty lumber and building, white oak trees can thrive for hundreds of years before falling over or felled by a logger. The trunks are rarely indeed white, but instead ashy gray. Identification is easy by looking at white oak leaves, which are fairly large and have five, seven or nine rounded lobes, and are lighter on the bottom than on the top. Acorns fall in September after maturing for a year; animals that like to eat these carbohydrate-rich snacks include fox squirrels, red squirrels, black bears and wild turkeys, just to name a few. White oak is found alongside northern red oak and sugar maple and can handle growing in rocky soil. Northern red oak (Quercus rubra) The northern red is the quickest-growing and most massive oak tree in the Hudson Valley, producing reddish-brown lumber that is almost as strong as white oak and is likewise used for heavy-duty construction projects. The trunk has a wide girth and a short bole (the bottom section of a tree trunk, from the end of the leaves to the ground) with gray-brown bark. Its leaves are big and wide with seven or nine toothy, bristle-tipped lobes that are dark, shiny green on top and a paler, softer feeling underneath on the bottom. Northern red oak’s height stays below that of white oak, never exceeding 100 feet, but the circumference in some specimens has reached six to eight feet after living hundreds of years. Like white oak, it persists in low-nutrient soil and grows alongside eastern white pine, white ash, green ash, aspen, sugar maple and other oak species. Northern red oak needs open spaces in the forest canopy to survive and cannot regenerate under shade. It bears acorns every two years: that which are roughly the same size as white oak acorns, but have less of the nut enclosed in the bottom “cup.” Deer, mice, domestic hogs and black bears consume a lot of these fallen nuts when they drop in the autumn. Oddly, the gray squirrel prefers the bitter flavor of northern red oak acorns to white oak nuts, unlike its aforementioned cousins. Fall leaf colors range from yellow to maroon red, and spring leaves turn pink before going summer green. Eastern cottonwood (populus deltoides) Found alongside moisture-rich areas, such as alongside the Mohawk River and Six Mile Waterworks Park, eastern cottonwood grows in floodplains and can be anywhere from 30 to 190 feet in height. Its roots can go a hundred feet below ground, spreading horizontally to cause structural damage to houses and pavement. It’s able to reproduce asexually when parts of the tree fall off, and when cut, its stump bursts into new sprouts; that said, it grows fast and has a short life. Eastern cottonwood as a material is soft and weak, but has use in producing pulp and shipping boxes. Its heart-triangle-shaped leaves are medium-sized, and in early spring, clusters of fruit capsules develop; red berry-like fruits are male catkins, while the female catkins similarly droop down off the tree, but take the form of yellow flowers. Later in spring, the tree’s fruits ripen into tiny mats of fine white hairs and blow into the wind like cotton balls. When a cottonwood twig is broken, it emits an unpleasant odor—this is one way to double-check that you have the right tree. Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) Best known as the tree whose leaf is the iconic silhouette on Canada’s flag, sugar maple is also the official state tree of New York (…and Vermont, West Virginia and Wisconsin) and the plant that makes maple syrup possible. Sugar maple leaves have three to five shallow lobes that taper out into wide-spaced teeth, and the underbelly of each leaf is a paler shade of green than its shiny top. Specimens often exceed 100 feet in height and may live for hundreds of years—hundreds of autumn seasons to appreciate the red, orange and golden yellow fall leaves on healthy, shiny brown twigs. With such a long lifespan, trunks of sugar maple make fantastic lumber for housing, furniture, fine interior finish and high-grade fuelwood. It is a forest tree that can handle being under the shade of a bigger tree and can live as an understory plant below a closed canopy, racing to grow toward any light that peeks through the leaves. Trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) Trembling aspen or “quaking aspen” is one of the most common trees in North America, located across Canada and in the cooler, northeastern regions of the United States. Known colloquially simply as “aspen,” it is distinguishable by its narrow, pale trunk, which is smooth-looking with black knots. In autumn, the leaves go from green to golden yellow. Aspen is shade-resistant, meaning it cannot reproduce under its own canopy. Its wood is very soft, and used as pulp to make light paper products. Animals of all shapes and sizes enjoy eating aspen bark and branches, from mice to rabbits to deer. In addition to food, birds and mammals alike use the trees for shelter, shade and nesting. After a fire, aspen repopulates using a shared root system: carbohydrate-loaded stems from colonies of aspen that burnt away can quickly regenerate into new growth. When fall rolls around, its flat, wide leaves turn yellow. Black willow (Salix nigra) Also called swamp willow, black willow thrives in swamp-like conditions and alongside riverbanks, unless a specimen can get a lot of sun on sandy soil, along with a fair amount of rain. Black willow usually grows over 40 feet tall and is wide at the crown, with long branches with narrow, finely serrated leaves cascading all around a dark trunk. This species isn’t used for lumber; instead, the splinter-resistant, soft wood is turned into pulp for paper and shipping boxes. Its branches do not droop like black willow’s more famous “weeping” cousin; this variety has a perkier look. Fruit, in the form of tiny, smooth capsules, ripens and falls in spring after collecting in bunches at the end of each branch.

4 Comments

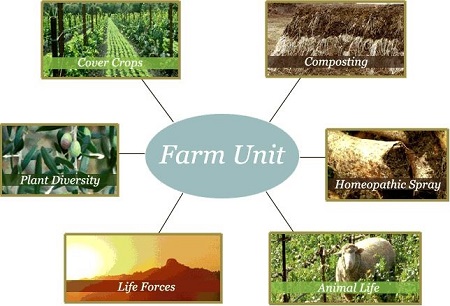

Biodynamics is a form of alternative agriculture that applies various principles of organic farming, while factoring in the optimal lunar and solar phases. It's a complicated field, but there's strong research showing positive effects on plant and tree sustainability, which lessens the need for tree removal. The best kept secret in biodynamics today is valerian preparation.

Rudolf Steiner, a well-known author, created a powerful agriculture course where he cited two problems trees and plants face that we have the ability to combat:

The Nelson farm in North Carolina was able to pick berries well into December by spraying valerian after every frost that autumn. As such, no tree removal was necessary. Heikke Marie Eubanks in Oregon was able to keep all of her gardens alive, following a series of four killing frosts in the spring. She added valerian to the finished compost (in the way Steiner indicated) and all of the plants fertilized with it remained untouched. So we have winter kill survival on the Nelson farm and frost exposure in the Eubanks garden. Valerian, when properly applied, cures both. What about lack of water? That would be drought. The best example of drought farming in the world is undoubtedly the Podolinsky farm in Australia with its 10 to 15 inches of rainfall per year. Alex Podolinsky, a pioneering biodynamic farmer, famously created 3 feet of topsoil using his own prepared 500 formula. This formula as it happens applies valerian to a finished horn manure product. Just like the Eubanks finished compost that Podolinsky prepared, 500 is a colloidal carbon substance that can absorb, hold, and radiate a life force. Valerian protects both the life of the soil and the life of the plant from drought when used in the correct manner. What is the connection between winter kill frost and drought? Lack of water. Cold air is dry air. Frost (as freezerburn) will burn a plant just as drought (as fire) will wither it. The lack of water is the common element. The presence of valerian protects the integrity of the cell membrane under drought conditions, as distinct from temperature. Why then do so few farms report these remarkable effects of valerian use? Because valerian must be applied to a finished colloidal compost product or to a colloidal soil to take effect. As a liquid dilution, it must be absorbed by something in order to transfer its force. Valerian applied to the freshly made compost pile simply disappears as the substance of the pile heats up and undergoes transformation. Steiner is quite clear about this in his instructions for valerian use, stating, "Before using this so treated fertilizer, we are to greatly dilute in warm water the juice of the blossoms." And how many of us are using warm water to make valerian? Notice that you can't use compost as a fertilizer until it has become a finished product. Valerian produces astonishing results only if it is applied and used in the right way, as indicated. How did we go astray in using valerian? Nearly a century of following instructions for making and using it without some insight into how it actually works makes it hard to correct errors, evaluate results, or spark enthusiasm to explore its possibilities. Think what this could mean to California agriculture in the next drought, or upstate New York fruit tree farms during the bud killing waves of spring frost, or the Florida orange grove harvest in the fall. Valerian is the answer. |

AuthorJoe Stevens writes for numerous publications on the latest in organic and bio-dynamic agriculture research. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed